The following interview with Marian Nummert was published in the Estonia Postimees newspaper by Trinokl. It is

an interview for Trinokl and published in the Postimees supplement on 31.05.2025:

“I’m an all-round student of life, and I’m particularly interested in soil and the inner logic of how nature works as a whole.” Why soil if you are interested in the whole?

The whole is made up of parts. I’ve always been interested in the ‘edges’, the paths that are perhaps less walked but have the most diversity. It was at the intersection of agriculture, ecology and permaculture that I discovered soil biodiversity and realised that, although it is one of the most biodiverse communities on the planet, we still know too little about it. Soil is where all the problems of our time meet, and probably the solutions too. When soil is seen and treated as a whole, the greater wholeness of nature becomes clearer. Just as when you look into a fractal you see repeating patterns, so it is in nature – wherever you look you see interwoven wholes at work. A closer look at the soil reveals the places where we have room for improvement as humans, as cultivators and as shepherds of nature.

If you look at human existence on the planet, for most of the time we have been hunter-gatherers feeding mainly on perennials for plants. Over the last 10 000 years, there has been a sharp shift towards annual plants, which now make up a very large part of our diet. However, in many ways they act quite differently on soil. For example, perennials release 30-50% of the energy produced by photosynthesis as root exudates, while annuals release only 20-30%. This illustrates the different relationship with soil biota. We constantly need to think in terms of a long-term relationship, involving more generous sharing and continued support for each other. Annuals mostly need weed-free cultivated soil, which in today’s context of conventional farming also means soil fertility loss. How much permanent loss can we afford? Maybe we could eat more perennials and self-sufficient plants instead…?

Perhaps our health would be better, our agriculture different and our culture more sustainable? These are the places where the whole intertwines – where soil becomes intimately connected to human life yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Marian’s home garden. Photo: Kertu Ojaveski

One common claim is that, at current rates of soil degradation, the fertile topsoil could disappear in about 60 years. Why don’t we know more about soil loss?

Soil hasn’t been sexy. People don’t usually think about how soil is linked to so many other issues, such as health, environment, security, climate, water. For example, agriculture uses about 70% of our drinking water – much of which we simply dump on the ground. If the soil doesn’t work as it should, water is washed through the degraded soil and it doesn’t get cleaned. All the pesticides and fertilisers that are used will reach the groundwater faster the less living organisms there are in the soil – the part of the soil that makes it (fertile). A soil that is functionally rich in living organisms can purify water. Pesticides in groundwater show that many soils are no longer so. Water is what is predicted to be in conflict for the foreseeable future – it would be foolish to exacerbate these problems by further destroying the soil. But this is what is happening now.

Soil is also known as the ‘skin of the planet’ because it protects and nourishes our living systems. How will this vital layer disappear?

The Estonian language is primordial – it knows only one soil, and the word “soil” generally means soil that contains life and in which plants grow. These same plants are the organisms that contribute to the creation of soil. Without plants, there would be no soil, because plants photosynthesise and distribute the surplus from photosynthesis – sugars – to the soil organisms, which in turn provide the plants with the nutrients they need. Carbon is the key word here – if you don’t have enough carbohydrates (plants make sugars, or carbohydrates and oxygen, from CO2), the soil organisms don’t have enough food and die.

Humans contribute to this in many ways. Firstly, we are removing too much carbon from the soil – harvesting also removes all the chemical elements that make up the crop from the field – either for animal feed or just to burn (in other parts of the world) so it doesn’t interfere with the next sowing. In Estonia, farmers mostly grind up the straw they produce, which remains on the ground as mulch. If there is not enough biota in the soil, this mass is a bit of a problem, as it tends to get in the way of machinery when direct sowing is applied. There are spraying agents that stimulate straw-degrading organisms. Taken together, this again points to problems for soil biota. Forest soils may also have such a problem, as large amounts of woody biomass, which was not previously removed from the forest during felling, are currently being burned off in boilers. I don’t know if anyone has done enough research on this.

Secondly, we are turning the soil bare- ploughing destroys the soil structure and leaves the soil unprotected from the weather. For nature, bare soil is like an open wound – it needs to be nurtured back to health! Man’s skills and power to achieve black soil have grown and nature must accept our decisions. Autumn ploughing leaves the soil to eroding forces – wind, rain and snow – all of which wash our soils into streams, rivers and eventually the Baltic Sea. There is already an overabundance of nutrients in the Baltic, so the problem is getting worse. Uncovered soil means no plants and their roots. Plant roots, on the other hand, contribute to the soil structure. Undisturbed soil allows the growth of soil fungi, which, among other things, are involved in the production of ‘soil glue’, or glomalin, which is considered to be the real builder of soil fertility. Glomalin makes up a large proportion of soil carbon and helps to form soil humps.

Third, we apply mineral fertilisers and pesticides to the fields. Fertilisers are salts, which act on soil organisms in much the same way as table salt does on snails. Pesticides, which are designed to repel various pathogens, also destroy beneficial soil life to the same extent – they are not selective, just as antibiotics are not. If anything is against life, it is against life, really.

If, according to the results so far, the diversity of soil fungi is highest in ploughed fields compared to the intensively managed cropland, and yet we know that ploughing is detrimental to soil biota, one can only wonder what the diversity would be in fields that are not ploughed and whose biota is not destroyed by fertilisation and pesticides. Such production fields are almost non-existent in Estonia, because organic farmers plough and do not direct sow, and conventional farmers tend to move towards direct sowing and more spraying. We need to start introducing a whole new set of knowledge and practices if we want our children and grandchildren to be able to eat something grown in the soil!

Fourth, we are overgrazing our soils – animals can be both destructive and creative agents in the soil. The general perception is that overgrazing has led many areas to desertification. The simple conclusion would be to remove the animals from the soils (which is largely what has been done in Estonia), and this is what Allan Savory (1935-born ecologist and advocate of holistic farming – ed) thought when he was involved in the destruction of 40,000 elephants, which he claimed were contributing to desertification in Africa. He later realised he had been wrong. Moving herds of animals are the reason savannas work. The logic is that in nature, large herds of animals are constantly moving around – they are hunted by predators and have their own migration cycle. They eat away at an area and only return to it when new vegetation has grown. Conventional grazing, however, is such that the vegetation the animals trample on and eat cannot regenerate and the soil slowly erodes away. When humans begin to mimic what happens in nature, they graze differently – large numbers of animals in a small area for a short time. In this case the animals are in constant rotation on different pastures thereby increasing soil life.

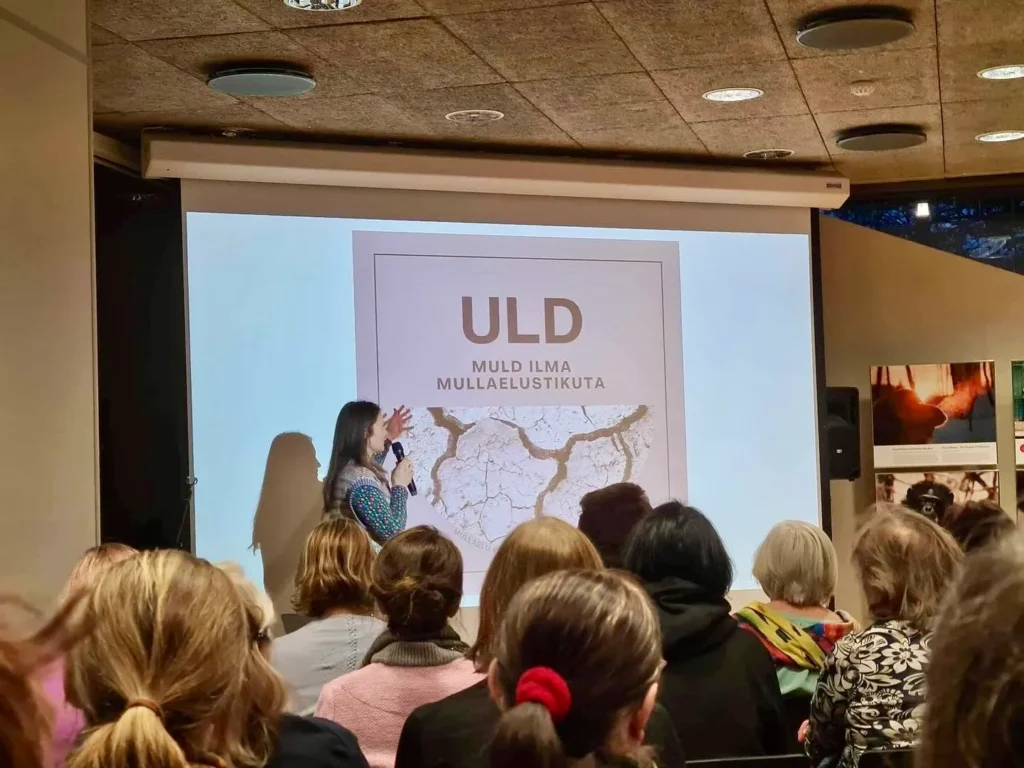

In order to understand the difference between a rich and a poor soil, a word is needed to describe a soil with reduced and almost non-existent soil fertility and soil biota. The English word is dirt. In one discussion, we came up with the word in Estonian “uld”, where the “m” has been dropped to indicate the absence of soil life (M stands for microorganisms). In essence, ‘uld’ and ‘muld’ are the same, but functionally very different. ‘Uld’ (dirt) can become ‘muld’ (soil) by supporting and allowing all the necessary groups of soil organisms to re-exist and function in the soil.

Introducing the word ULD at the Tartu Nature House. Photo: Ann Roost

The statement that civilisation lives and dies with its soil reflects the importance of soil fertility for food production. What actually happens when soil fertility declines and disappears?

If it weren’t for soil organisms, all these decomposers, one can only imagine the mountains of organic matter that would be floating around us. If it weren’t for these decomposers and plant feeders, the plants wouldn’t grow and then the soil wouldn’t grow, because the plants feed the soil life. For humans, reduced soil fertility means that the same amount of food cannot be grown on the same amount of land. The last of the forests will have to be cleared… and then we will still face desertification, because forests attract rain. Maybe we are a bit better off here in a cold and wet climate than in the warm and already dry parts of the world. But we won’t be doing well if everyone is rushing here in search of every last bit of soil and food. We are still in the same boat. Nobody knows what will happen when the balance of the planet shifts on a large scale.

Another issue is water – if the soil no longer filters water, we’re in trouble. You keep pouring wastewater on the ground – modern septic tanks and even bio-treatment plants rely on it – but there is no new clean water coming from anywhere, we need to keep purifying the water. It is soil life that has helped us so far and hopefully will continue to help us to keep the waters pure.

Seed collection is part of permaculture. Image: Kertu Ojaveski

From what you say, the situation seems to be pretty crazy and we don’t realise how serious it is. What can we do to avoid the chaos and destruction towards which we are heading?

Nature is always ready to recover, as long as man no longer interferes and, at best, supports recovery.

There is only one path we can choose – to work with nature, in partnership with soil microbes, fungi and all other soil dwellers. This path must be chosen at every level – global organisations, the European Union, public authorities and legislators, universities, food growers and gardeners.

The farmer is not to blame – this is our collective responsibility and, above all, the wisdom and action should come from the upper echelons of society, because that is where our most educated should be.

The farmer is mostly a conservative, because he must constantly act according to the season and also according to the wisdom of his ancestors and common practice, because if he were to doubt everything all the time, he would miss the spring sowing and the harvest. After all, we want to be able to buy flour and potatoes from the shop at any time. The farmer must make his decisions with an eye to the future, because the equipment he buys will determine whether he can carry out direct sowing or whether he has to plough the land first. The equipment purchased will last for at least five years.

There must be guidelines from universities and ministries to help farmers make good choices. However, the reality is often that it is the people who are actually in touch with the land who are the enthusiasts, who can see problems coming and who cannot sit on their hands. The permaculture movement, for example, already touches millions of people globally, all of whom think it is time for a change and are constantly acting on the idea of soil fertility. Everyone on the planet can make better choices if they have the stamina and skills.

Today’s capitalist society favours those with more money and directs people to make primarily economic choices. Money and empowerment go hand in hand. That’s how the big chemical companies in Brussels have set up lobbying operations close to those in power. It is quite interesting to read on Bayer’s website about environmentalism and thinking about biodiversity, when at the same time its products and those of other similar companies (Syngenta, BASF, Dow and countless others) are surely a major destroyer of soil life globally, and the information disseminated with their corporate money is ringing in farmers’ ears and guiding farming practices.

While in Europe there is still some control over what chemicals can be thrown on the fields, in the developing world all the toxic cocktail that no longer passes through our legislative filters is being diverted to the developing world. As a result, local seeds and traditional ways of life are being destroyed, not to mention human rights. Money is being funnelled into the corporate warehouses of our ‘highly developed’ countries without any ethics of substance. Next to this, the EU’s pursuit of clean energy, food and the environment is very hypocritical. A simple example: at the end of the year, you have to become a detective to find gingerbread that does not contain palm oil, the production of which destroys the habitats of orangutans and many of the world’s rare species, and turns rainforests into monoculture fields.

The biggest challenge for humanity is to keep the focus on a forward caring course, both politically and substantively. Simply put – how to make sure that actions and thoughts are aligned and working towards a common goal. In the meantime, the question remains: are such contradictions one of the hallmarks of a post-truth world, or one of life’s hardest to live by – be honest?

Greenhouse – gardener’s office. Photo: Kertu Ojaveski

Good enough. Let’s say everyone understands the need for change, but the question immediately arises: what do we do with this knowledge?

We need to stop ploughing and not replace it with pesticides. Plant nutrition needs to be brought into line with soil biota. Obviously, balanced soil biota feeds plants better than artificial fertilisers. Moreover, we won’t have artificial fertilisers for ever, phosphorus reserves are already starting to run out, and this is why mining our mineral resources has become an issue.

Excessive grazing (or cramming animals into barns) needs to be stopped, and we need to allow animals to help us restore soil life. Man-made fertiliser (yes, the stuff we flush down the toilet!) should be used as fertiliser, not to pollute drinking water. Then it will immediately become clear that man must not poison his own body, otherwise these poisons will soon be on the menu.

In the longer term, plant breeding must no longer concentrate on quantity, but on the quality of the food and the characteristics of the plants, which help them to cooperate better with the soil organisms. Scientists and farmers should make a concerted effort. Fortunately, good examples already exist. For example, our family farm is collaborating with soil ecologist Tanel Vahter from the University of Tartu to find out about the situation of soil-dwelling fungi in farmland. As part of the Estonia in Nature project, we are creating a variety of grass strips, hedges and tree rows at the edges and in the middle of fields to allow soil life to thrive without disturbance.

Food pricing systems and policies must start to take into account the cost of damage to the environment and to health – food produced in a way that does not respect nature must not be the cheapest and most accessible! This is up to policy makers! Support systems and the like determine a lot. Estonian farmers are much more dependent on subsidies than in Europe as a whole – ours 72%, the Union average 33%. In Estonia, for example, no more organic land is currently being registered for organic payments. At the same time, organic production does not always mean preserving and growing (soil) biota. There is room for development! Soil knowledge is currently not even sufficient to be able to adequately consider soil biota in the context of land use and food production. It is even more astonishing to think that people are spending billions to study what is happening on Mars, and how to get there, and whether there is soil there, while we are destroying the most precious natural resource on our planet. My farmer brother commented here that direct sowing is probably at least as difficult as going to Mars.

Soil and plant investigation

At the same time, it is said that the more skilful use of technology and smart solutions can also make conventional farming more sustainable.

It seems that people are starting to realise that more technology doesn’t actually make anything easier or more sustainable. AI can provide solutions, but at a cost – do we trade the integrity of our natural world for wind turbines, solar panels, power lines, pipes and waste disposal? There is probably a balancing point somewhere, but before making things more complicated, how can we make it simpler? Nature is an interesting teacher in this respect – the immersiveness of nature is so high that we can barely grasp it. At the same time, sitting under a tree and walking in the woods, everyone feels how life becomes simpler, worries smaller and existence lighter. Somewhere there are all the answers to our questions – in the realisation of paradox. As Bill Mollison has said: “While the world’s problems are increasingly complex, the solutions remain embarrassingly simple.”

You refer to one of the founders of permaculture, Bill Mollison. He has also said that in nature the best solutions are often the simplest, but it is their simplicity that makes them hard to spot. The role of permaculture, he says, is to help us find these simple solutions and integrate them into everyday life in ways that improve the quality of life for people and ecosystems. What would have to change in society to achieve better awareness and implementation of these solutions, to achieve a balance between the use of technology and living close to nature?

I can only share how I have come to notice the solutions myself – through observation and relating. It’s a long-established scientific method of inquiry. Nature is holistic, therefore it must be perceived holistically. The more attentive and open you are to yourself, the more the patterns of nature will reveal themselves to you. Nature reveals what has happened in the place you are looking at before and where the current changes are heading. The damage done to the soil is clearly reflected in the growth of plants, the presence of water in the landscape and its purity. When I get to know a piece of land, it somehow becomes part of my field of perception and I begin to sense what is happening there and how my actions can affect it both negatively and positively. Once the basic patterns of how nature works are manifested, they can be transferred to larger systems because they are like fractals – the same principles and patterns are there, both up close and from a distance.

In your opinion, how realistic is the transition to the application of regenerative agriculture practices in a significant part of today’s food production and where could we reach in the near future in Estonia?

I don’t think it’s realistic that we can operate on a planet without respecting the laws of nature for very long, so I don’t see any other kind of agriculture having a very long future. Regenerative agriculture is based on learning the logic of nature, guided by principles, not rules. This means that everyone has to find an appropriate solution to their own situation, use available resources wisely, and constantly adapt and evolve to changing circumstances. Just the way nature works.

Because human health is directly linked to the health of nature and the soil, people depend on how nature and the soil are doing. While farming and agriculture most directly interact with soil, land and nature, indirectly nature is an input to all sectors of the economy. The better we understand the logic of nature and are able to take it into account in our choices, the longer we will be able to live healthy and fulfilling lives here. Permaculture is about seeing solutions to problems, and offers systemic ways of designing to do so, so that we can make as informed choices as we can at the moment. There is no upper limit to working with nature, only the imagination.

Perhaps one day we will no longer have to call nature-based design thinking permaculture, because it is something that has become natural to us again. Estonians used to call it ‘peasant wisdom’ or something similar. Today, there are simply few of those peasants left, and society’s problems have grown and expanded.

The logic of nature does not change whether or not we as humans have understood and applied it[CD2] [MN3] . It is rather a question of whether we can reconcile the reality of nature with the reality of ourselves. As long as the result of our choices and actions is the degradation of wildlife, we will be operating in a virtual reality of our own making, out of harmony with what exists. Which will happen first – human culture in harmony with nature or the destruction of nature – is the key question. Everyone can at least make a choice within themselves and then follow the big game.

How has the practice and popularisation of permaculture influenced your life, has it been life-changing?

I can certainly admit that it has been life-changing for me. I distinctly remember my first encounter with a food forest on Vancouver Island, Canada. As a backpacker, it was a place where I could stop, stuff my mouth full of berries, learn about native plants and meet people who care about nature. When I found out that such a food forest was based on permaculture, I set out to explore. The dots started to connect and still do. Six years later, I gave a talk about permaculture to a hundred people in the Tartu Loodusmaja, and from there it has all just flowed further. I have shared my excitement and it seems to have infected others. Step by step the trail has revealed itself to me and I have followed.

Could you share with readers any moments or experiences from your permaculture journey that have been the most enlightening or inspiring, and how these experiences have influenced your thinking?

Once, when I was talking about the food forest, I was asked what the smallest but most impactful change could be (a permaculture principle). The answer came quickly, as I had done my fair share of experimenting and observing on my own patch of land: a stick placed in the field. There is nowhere for birds to perch in a monoculture landscape of annuals (read: field). If a stick appears, the birds can sit there. Sitting and taking flight are often accompanied by the shedding of droppings, which often contain plant seeds. This is how I have found raspberries, wild strawberries, cherries, willows and many other plants growing around the stick. In this same work lies another principle: if you take one step towards nature, nature will take ten steps towards you. And a third: start small, but start. In the context of this lecture, my answer stuck in the minds of many listeners, and we are currently testing this idea in the fields of our family farm, together with researchers from the University of Tartu, as part of the LIFE IP project ForEst&FarmLand (Loodusrikas Eesti).

Such inner discoveries, connecting the dots, linking principles to real life are the most refreshing. That’s why permaculture keeps inspiring me – there’s something to notice, to understand and to broaden my own understanding. These insights can in turn lead to actions that resonate with nature.

What practical advice would you give to those who want to experiment with permaculture on their own, even in their own back garden?

The first suggestion is to look at your garden – to get to know those who live in your garden; to notice the forces of nature at work and figure out what kind of relationship with nature do you want? Do you want to grow your own food or create an oasis where you can recover from the hustle and bustle? Why not both? The end justifies the means. Think through your goals and take actions that match them.

Permaculture recommends doing as nature does – keeping the soil constantly covered, supporting diversity and learning from your experience. Permaculture is not a recipe to be applied in every situation – permaculture is the art of catching fish. Skills come from experimenting and looking around your garden with an inventive eye. What resources are there? Maybe instead of throwing the leaves in the bin, you could let them turn to soil and build a brushwood fence out of the branches. Each garden could have a ‘zone 5’ where nature operates with minimal human intervention. Inspired by Mary Reynolds (Irish gardener and landscaper – ed), you could even leave half of your garden to nature – choosing to do acts of restorative kindness.

In your experience, what have been the most remarkable results of such set-asides and how have they contributed to your understanding of the wider impact of permaculture principles? Please give some examples.

Leaving to nature can be seen in several ways. If you don’t mow your lawn, you’ll soon find new plants to get to know and some to put on a plate, dish or vase. If a meadow is left unmowed and ungrazed for years, grassland diversity starts to disappear and long-lived grasses and a few other perennials take over – the existing diversity is lost. After a while, the first shrubs and trees begin to appear, and over decades and hundreds of years a forest develops, and the agricultural soil becomes forest soil. This is a natural succession, both above and below ground. However, human lifespans are not that long, and diversity is found in different communities, not only in primeval forests – in Estonia we maintain species-rich meadows alongside species-rich virgin forests and ancient peatlands.

From 2022, Türi is your home town. What opportunities does the small gardentown offer to live in harmony with nature?

Türi is exactly the right place to live right now – children can move independently between school and their hobbies; at the end of the street starts a forest where we can pick blueberries and blackberries and experience the forest in summer and winter. Türi’s (garden-loving) community is a diverse one, and I feel I have found my own people with whom to explore new frontiers and push the boundaries of possibility. Türi is in the middle of Estonia – no place in Estonia seems too far away, and if we approach it creatively, we are by the sea with the help of Pärnu River that flows by to the Baltic Sea.

Türi is the capital of spring – it helps to remember the power of budding, to poke around in the blooming spring sunshine, to find reasons to grow a school food garden and to promote a community garden.

What collaborative projects or initiatives have you seen or imagined that could further strengthen the connection between nature and community in the Garden City?

In my experience, the most important thing is human relations. There can be all sorts of ideas and perceptions, but the ones that come to life are the ones where people feel that it speaks to them and they want to be part of it and continue to be part of it. You can’t rush into a vibrant community and proclaim what’s “right” and that everyone should immediately understand it in the same way. Rather, you have to listen first, do your own thing, and then, when called, proclaim. At least that is what my life has taught me.

In Türi, there is a community association, house and garden called “KONN” (frog), of which I have now become a part, and I sense a lot of potential bubbling up there that will one day turn frogspawn into frogs. I also hope that the food garden at Türi Primary School will become both an educational and community gathering place for resilience. It takes time for ideas to grow into action – like a seed to grow into a full-grown tree. Perhaps the real fruit and the glory of the shoots will only be seen by future generations. We in Türi have traces of predecessors to be proud of and to draw support and inspiration from.

Nature and community – in each of us, these connections live in different ways. Some find nature by wandering alone in the woods, others by chatting with friends over a cup of tea, and others by tending to plants in their gardens. It’s the same with community – for some, it’s a supportive backbone, for others it’s going on a hike, for others it’s a trip to the sauna, for others it’s a soup supper at the community centre. Communities can’t be imposed, but they can be noticed and encouraged to thrive and grow. I hope we have the peacefulness and friendliness to notice and embrace our differences and diversities. Perhaps then, exactly the right things will happen here, so that one day we will be able to say for ourselves what has already been mentioned by some – Türi is the capital of Estonian permaculture. For the sake of balance, I think that titles do not matter if there is no substance; therefore, actions before words.

And a final question: do we still have hope?

Despite all that seems hopeless, it seems important to me to engage in daily self-care, which includes keeping hope alive. Depression is crippling, but an awareness of the situation and an attitude of looking for solutions to problems is invigorating. As long as nature is present and functioning in our current reality, we have the world’s best saviour and teacher at our fingertips. What you grow grows – if we focus our consciousness and actions on, for example, growing soil and working with wildlife and biodiversity, then much will continue to be possible!

Marian’s reading recommendations:

Looby Macnamara, “Cultural Emergence. A Toolkit for Transforming Ourselves & The World” (2021).

Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, Murray Silverstein, Max Jacobson, Ingrid Fiksdahl-King , Shlomo Angel “A Pattern Language” (1977).

David R. Montgomery and Anne Bikle “What Your Food Ate”

INFORMATION box

Marian Nummert (39) is a permaculture designer and educator.

Marian, who studied ecology, law, and permaculture design, has been teaching permaculture since 2015. Her first meeting to permaculture was seven or eight years earlier when she travelled in Mexico and Canada in 2008-2009. She has since studied permaculture in Estonia and Sweden and now doing her Diploma in Applied Permaculture Design with Nordic Permaculture Academy. Her training topics include, for example, sustainable living, introduction to permaculture, food gardening, soil biology, urban gardening, permaculture beds, etc. In October 2024 she was selected as Järvamaa county Educator of the Year.

As of spring 2024, Marian will also contribute to family’s grain farm that is turning towards regenerative agriculture (about 1200 ha).

0 Comments